Faculty Spotlights - Andrea Westcot

“I hope that [my students] felt seen, understood, and prioritized.”

Andrea Westcot, Instructor, Liberal Arts Department

What are some of your main goals as an instructor related to student learning?

I strive to create an exciting, inclusive learning experience for my students. I prioritize active learning, student engagement, and rigorous project-based learning. I tell my students, “my priority is your success” – and I work with them as a class and individually to help them reach their goals.

How did your teaching progress after you started teaching remotely?

I started with equal parts anxiety and hope.

My anxiety was based in two major issues. First, my courses prioritize discussion and active learning, such as small group work, embodied learning practices, and in-class research, writing, and workshopping. I knew that these practices – which depend on community and the intimacy of a classroom – would be interrupted not just by remote teaching but by all of our considerable anxiety about the world.

Second, this particular class content focused on the history of Baltimore. It is emphatically rooted in Baltimore (and Peabody, and Mount Vernon) as a PLACE. In being torn from the city, the course’s content became unmoored. Similarly, student research projects – ethnographic and historic research of specific places in Mount Vernon – would have to be completely overhauled.

My hope was based on the fact that I was already comfortable with many of the online tools. I hoped that because of that, I’d be better prepared to help my students succeed remotely. The course was already housed on the Learning Management System, and I had already planned to round out the semester with an online research and writing project.

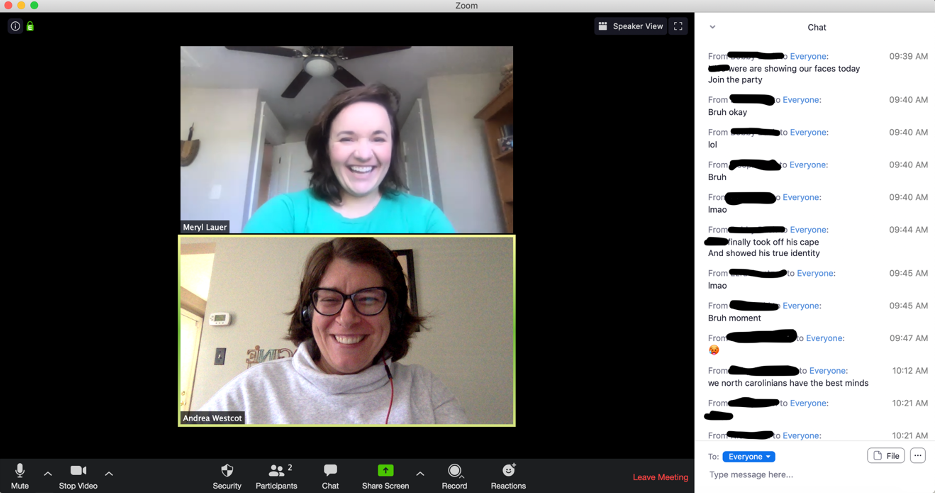

In this image, Drs. Meryl Lauer and Andrea Westcot lead a conversation with students. Note that the students are using the chat very informally. This was enthusiastically condoned by us. We found that allowing students to be silly, to make jokes, and to just have fun helped lift everyone’s spirits.

What is a challenge you’ve encountered while teaching, and how did you address it?

The biggest challenge I encountered was definitely student engagement. Obviously, we lacked the common ground of a shared space, and students were dealing with trauma. While students would “show up” for Zoom meetings if they could (and many showed up for every single class), it was hard to facilitate meaningful conversations. Too frequently, classes became more focused on a lecture format. For some students, structural barriers – lack of reliable internet, lack of private space, displacement, quarantine, illness – kept them from being able to fully participate.

I found that allowing for – and even encouraging – silliness, fun, and informality in our class Zoom meetings helped improve those sessions. I quickly realized that the students authentically missed each other, and missed Peabody – and our class was a chance for them to see each other. Rather than trying to clamp down on this, I encouraged it. For example, I encouraged students to use the chat not just for formal questions, but to make jokes, pass notes, and be silly. (See attached screenshot.) I found that this actually increased students’ engagement in the course content – the chat kept them involved and on their toes.

More importantly, I found that working with each student as an individual was key to addressing these issues. Even if Zoom was ill-suited to class discussions, it proved remarkably useful for one-on-one conversations, research consultations, and writing help. I required students to meet with me one-on-one at least once; I found that they really valued that time, and I met with most of my students multiple times (including several with whom I met weekly). I frequently sent individual emails to each student on my roster in order to check in with them, offer support, and congratulate them for successes.

What does your teaching setup at home look like?

Luckily, we have a home office in our house – with a door! While teaching my classes, I was able to shut the door so that my children knew that I shouldn’t be disturbed. Luckily, I have my own laptop, a printer, and fast internet to help facilitate my work. That said, with two parents working from home, and two children doing school from home, we often had to strategize teaching, working, and learning, especially when all four of us needed access to devices simultaneously.

What advice do you have for other faculty?

Early on, I found that “academic Twitter” was a really useful resource for advice, particularly around setting appropriate expectations. These two posts were particularly useful:

- Please Do a Bad Job of Putting Your Courses Online

Despite its title, this blog post set expectations for how to approach emergency remote teaching in a reasonable and humane way. - ‘Nobody Signed Up for This’: One Professor’s Guidelines for an Interrupted Semester

I added a copy of this document – a set of four “principles” for emergency remote teaching – to my syllabus. It served as a statement of principles that both me and my students could use to guide our movement forward. I found it uplifting, humane, and inspiring.

How do you want your students to remember this time after they have left Peabody?

I hope that they remember their time in my course as a welcoming, humane space where they were able to learn, think, develop, and express their ideas authentically. I hope that they felt seen, understood, and prioritized. I’m realizing that this is the same hope I have for a “normal” semester.