The Creative Wire

Project Poetic Justice Gives Incarcerated Youth a Voice—and a Second Chance

Sept. 19, 2025 | by Ryan Alexander

Edited by Lara Pellegrinelli

“At sentencing hearing. Waiting for his case to be called… I’ll send you the link in case you want to log on, but no pressure.” – text message from attorney Jane Patterson of the Initiative for Youth Justice in Washington, D.C., June 13, 8:45 am

It was a Friday morning, and I was visiting my brother in Brooklyn. I’d just gotten back from a run in tree-lined Fort Greene Park, leaving enough time to shower and start my day. The last thing I expected was a text to pop up inviting me to a sentencing hearing for a resident at the DC Jail.

The hearing was for Shane, a resident of the A5D unit and student in Project Poetic Justice, the 10-week educational program I launched at the jail the previous spring. Each Tuesday, students met with teaching artists to brainstorm original poetry and figure out how to set it to music. The program was run with support from the Maya Angelou Public Charter School on the DC Jail’s campus and Free Minds Book Club, with funding from a Peabody Launch Grant, the Petey Greene Program, in-kind contributions, and crowdfunding.

I’d only ever attended one sentencing hearing before, for a longtime student named Josh. That cold, bureaucratic proceeding ended with an 18-year federal prison sentence. I’d learned then how important it was to show up for students at such critical moments.

So, I logged on for Shane, hard to miss in his bright orange jumpsuit, seated between two black-suited attorneys. He was clean-shaven, freshly buzzed, and intently focused on the judge presiding at the podium.

Our first encounter hadn’t been so encouraging. On a staircase outside dingy cells, he looked me over and said flatly, “Not interested in a music program and don’t know much about poetry.”

I honestly wasn’t sure if the material would resonate with a group of 18 to 24-year-old men.

Thankfully, Ms. Kelly, a housing unit coordinator, reassured me: “Ignore him. He’s one of our best and will participate.” Sure enough, on the first day of class, Shane was front and center, pencil in hand. He soon emerged as a leader, drawing in the entire A5D unit of about 20 young men.

Little did they know, the project almost didn’t happen. Despite my years of professional experience as an educator working with incarcerated youth and ties to D.C.’s Department of Corrections (DCDOC), weeks of emails went unanswered. I had a curriculum, schedule, monitoring tools, and a roster of poets, composers, and singers, but no access. At the last minute, the Petey Greene Program, already cleared to operate their tutoring program in the jail, became our sponsor. With little notice, I had to miss work to complete 40 hours of DCDOC training. After an avalanche of paperwork, the doors finally opened.

A5D has no classrooms, which meant working directly within the students’ living quarters. Amid the sounds of running showers, a blaring TV, beeping microwaves, the crackle of correctional officer walkie-talkies, and the chatter of early-evening phone calls, students tried to concentrate. It’s a bit of a miracle that anyone was able to hold focus long enough to write. On two dates, safety-related incidents left the unit on full or partial lockdown. As a result, students were locked in their cells the majority of the day, and “shake downs” delayed class by over an hour.

Most weeks, students arranged oversized, light-blue rubber furniture around a long conference table, creating a sort of makeshift classroom. They met in small groups with teaching artists to explore their thoughts and draft poems, then try to set these to music. The topics were wide-ranging and oftentimes unexpected. Dionté wrote about his children—a daughter “like a queen of a home,” a son like “a king on the throne.” Jay addressed his internal struggle to find mental clarity and freedom while incarcerated.

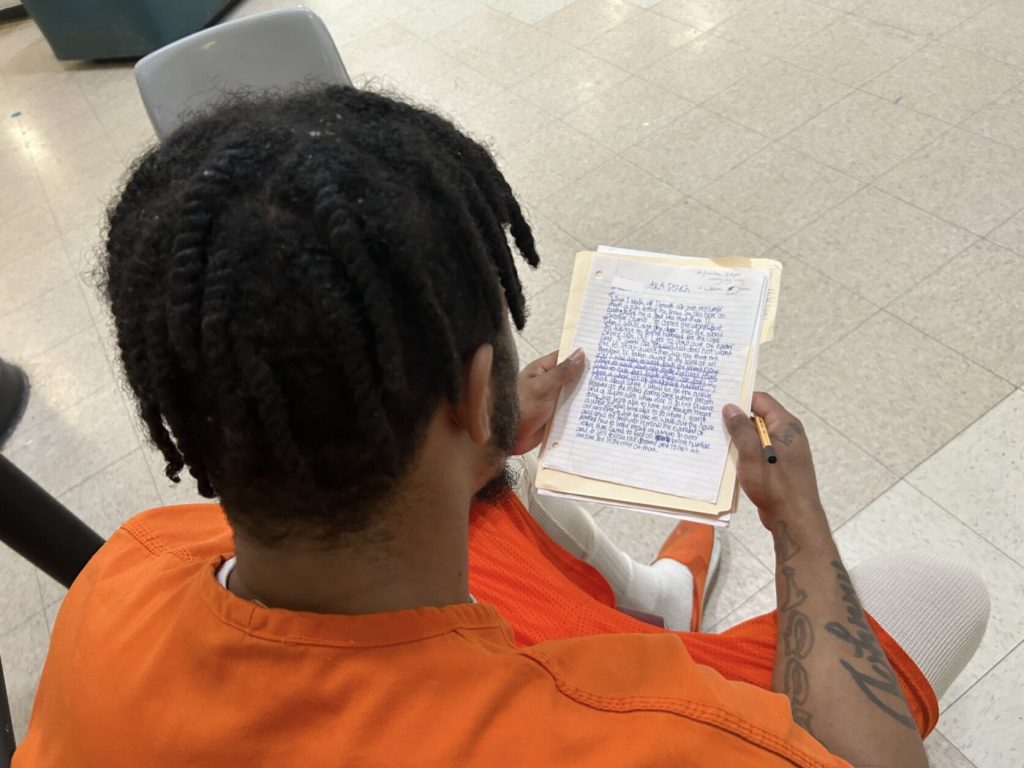

Shane’s narrative poem reflected on redemption, expressing hope in “another chance to correct wrongs” and to still follow his dreams. No matter what was going on around him, he continued to engage, even working with tutors through his locked cell door, exchanging ideas over the whirring of fans and shouting of other residents.

I vividly recall the sixth week of the program, when students and composition tutors huddled around a synthesizer in a cramped office. We chatted about goals, dreams, family, and for just a moment, forgot our surroundings. These conversations allowed us to see the men beyond their circumstances and helped us craft character statements for their attorneys.

Uncertainty lingered until the end. Final performances were scheduled at the jail and at Washington’s Church of the Epiphany. A sudden staffing shakeup ordered by D.C.’s mayor nearly canceled the jail performance, but the education department generously stepped in, unpaid, to keep it alive. At the Church of the Epiphany, family members, local community leaders, formerly incarcerated individuals, and friends filled the room.

Project Poetic Justice ultimately engaged more than 30 artists: poets in the Johns Hopkins MFA program, Peabody composers, published authors, professional vocalists, and more.

The response was overwhelming; many offered their talents for future projects. Coverage by WTOP reporter Scott Gelman—an article, radio segment, and video titled “‘I’m locked up, not washed up’: Young people incarcerated at DC jail get poetry, music lessons”—helped amplify the program’s impact. To this day, I hear that students are still talking about the program, and attorneys and artists continue reaching out to collaborate.

But perhaps the program’s most heartfelt victory was Shane’s. By the time of the hearing, it had only been 15 weeks since I’d met him. I didn’t know—or want to know—his charges. During the proceedings, the judge referenced the news article and highlighted Shane’s character statement, which I had co-written. As she spoke, I thought about how Shane told me that poetry and music helped him connect with his emotions in new ways, underscoring the deeper impact of arts education.

The hearing lasted just 20 minutes, and I found myself wondering what sort of bureaucratic red tape might still lay in Shane’s path. But soon after, Attorney Patterson texted: Shane was being released immediately. His community service hours were forgiven because of his participation in Project Poetic Justice.

“So amazing!” she wrote. “The judge watched the video about your program. That made such a difference. And the letters you all wrote were an incredible touch. Thank you so much.”

What a contrast to Josh’s hearing. Shane walked free—a reminder that the system can actually work to uplift a young person. I had wondered from the beginning if music and poetry could meet the urgent needs of incarcerated youth. Shane gave me hope that they can make a difference.

Ryan Alexander

Vocal Performance

MM ‘24

Ryan Alexander is an artist and activist whose work spans art song, musical theater, and film. Guided by his background in education and social justice, he has premiered new works, launched Project Poetic Justice at the DC Jail, and performed with ensembles including Cerberus and Dualis.